Streaming the Classics/Requiem—Verdi

Do you ever type a streaming query in Roon for a classical work and are overwhelmed by the choices? Rather than clicking on any old recording or the first one you see, Audiophilia will make things a little easier for you and do the heavy listening.

These choices are for streaming only. Is the best in streaming also the best vinyl recording and performance? That’s for another article.

A few criteria:

Recording must be on Qobuz and/or Tidal HiFi.

It does not have to be HiRes or MQA.

No more than ten recommendations in no particular order, then my top three for streaming in order of preference.

Here are 11 recordings of Verdi’s Messa da Requiem found on Tidal/Qobuz; I will list them below—no hierarchy intended. At the end of the review, with some necessary historical background offered to assist the audiophile, I’ll select 3 recordings that stand out for this reviewer.

1. Antonio Pappano Orchestra Coro Dell’ Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia/Anja Jarteros, Sonia Ganassi, Rolando Villazon, Rene Pape. EMI, September 4 th, 2009 release date.

2. Semyon Bychkov WDR Sinfonieorchester Koln, WDR Rundfunkechor Koln, NDR Chor, Turin Radio Chorus/ Violeta Urmana, Olga Borodina, Ramon Vargas, Ferruccio Furlanetto. Profil, January 1st, 2007 release date.

3. Sir Georg Solti Wiener Philharmonikers and Wiener Staatsopernchor/Dame Sutherland, Marilyn Horne, Luciano Pavarotti, Martti Talvela. Decca, originally recorded 1967; January 1st, 2006, release date.

4. Carlo Maria Giulini Philharmonia Chorus and Orchestra/Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, Christa Ludwig, Nicolai Gedda, Nicolai Ghiarurov. EMI Classics, 1963-64.

5. Jesus Lopez-Cobos London Philharmonic Choir and Orchestra/Margaret Price, Livia Budai, Giuseppe Giacomini, Robert Loyd. BBC Recording, September 1st, 2010, release date.

6. John Eliot Gardiner Orchestre Revolutionnaire et Romantique and Monteverdi Choir/Luba Orgonasova, Anne Sofie von Otter, Luca Canonici, Alastair Miles. Phillips, April 11th, 1995 release date.

7. Arturo Toscanini NBC Symphony Orchestra and Robert Shaw Chorale/Herra Nelli, Fedora Barbieri, Giuseppe Di Stefano, Cesare Siepi.

8. Daniel Barenboim Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Chicago Symphony Chorus/Alessandra Marc, Waltraud Meier, Placido Domingo, Ferruccio Furlanetto. Warner Classics, January 1 st, 1994, release date.

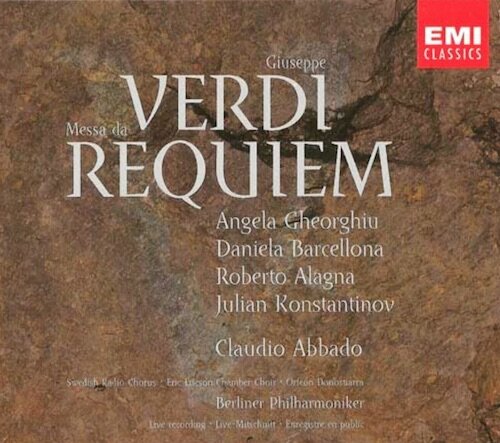

9. Claudio Abbado Berliner Philharmoniker, Swedish Radio Choir and Eric Ericson Chamber Choir/Angela Gheorghiu, Daniella Barcellona, Roberto Alagna, Julian Konstantinov. Warner Classics, September 15th, 2001, release date.

10. Valery Gergiev Kirov Orchestra and Chorus/Renee Fleming, Olga Borodina, Andrea Bocelli and Ildebrando D’ Achangelo. Philips, December 16th, 2003, release date.

11. Riccardo Muti Philharmonia Orchestra and Ambrosian Chorus/Renato Scotto, Agnes Baltsa, Veriano Luchetti and Eugeny Nesterenko/EMI Classics and Warner Classics, 1979 recording remastered 1995, August 9th, 2011, release date.

The story is well known; the details have been discussed often since the work’s inception and first performance. Both the background to Verdi’s Requiem and the piece itself, illuminate this extraordinary period of time in Italy’s road to nationhood. The fiercely proud struggle of the unique voice of Italian music, of which Verdi the composer was so essential, acts as a homage to Verdi’s contemporaries of the Risorgimento whom he so loved and admired. Perhaps the most beloved of them all was the writer and patriot, Alessandro Manzoni, to which the great Requiem is dedicated.

So profound was Verdi’s admiration for the pious and devoted Manzoni that when Giuseppena, Verdi’s wife, finally arranged a meeting between Verdi and his idol Manzoni, he wrote after, “I would have gone down on my knees before him if we were allowed to worship men.”

And so when Manzoni died in 1873, Verdi felt “a need of the heart” to not only honour this great man but to offer a public testament to the burgeoning natio, a very public and Italian farewell to one of the greatest of their sons, voiced in that musical tradition that Verdi himself helped to create.

Verdi completes his Requiem Mass in April 1874 and conducts the first performance May 22nd, 1874, at the church of San Marco in Milan on the one year anniversary of Manzoni’s death. The musical resources consist of 120 choristers, an orchestra of 100, and 4 of the leading Italian operatic soloists of the day. Interest from this first performance is so great, the Requiem is given 3 more performances at La Scala Theatre; these performances, without the dampening effect of ecclesiastical trappings, allow the Milanese public to hear the extraordinary power of this work unfettered. Their response is extraordinary; even during the performance there is unbridled applause for the inspiration of the melodies, often the enthusiasm turns to uncontrolled roars of approval.

Verdi’s Requiem becomes one of the most performed concert hall Requiems of all time, joining the illustrious company of the Mozart/Sussmayr Requiem. Yet, much unnecessary controversy has been spent, decrying Verdi’s rendition of the Requiem as too theatrical—too secular, too little sacred of nature. This observation, perhaps buttressed by Von Bulow’s original acerbic comment that Verdi’s Requiem was “…opera in ecclesiastical garb,” belies an historical ignorance of the evolution of the Requiem in the 19th century; for, after Berlioz’ Grande Messe des Morts of 1837, the Mass was no longer just a vehicle for private mourning, but could be now placed in the hands of the nation to commemorate its great sons and daughters. Verdi’s Requiem is in this line of evolution—from the cathedral to the concert hall to commemorate the best of the nation state. And as Hanslick stated, as a rebuttal to Von Bulow’s comment, Verdi wrote a Mass expressing the traditional liturgical text in his unique vocabulary, in the emotional musical language of the Italian people, giving evidence of Verdi’s consummate compositional skill for theatre in commemoration of one of its greatest sons.

Verdi’s power to evoke the deep contradiction in the Roman rite—God’s eternal love for Man and God’s self-definitional character for true justice—is superbly captured in the music, unlike any Requiem before or since, in my opinion. This is almost impossible to conceive of in a musical sense, yet Verdi pulls it off—on his terms. Now, let’s have a look at some of these very fine recordings.

Toscanini is the “granddaddy” of the Requiem because of his personal association with Verdi—Toscanini played cello under Verdi at the premier of Aida and led the Requiem himself in 1902 to mark the first anniversary of Verdi’s death. Toscanini made three recordings of the Requiem, one in 1938, one in 1940, and the famous 1951 live recording with the NBC Symphony Orchestra and the Robert Shaw Chorale. Toscanini was not at all impressed with recorded sound and had rehearsal clips spliced into the final release. The main difficulty, even with the final release, is the sheer unbalanced volume; soloists are abnormally loud at times and then disappear under the modest weight of the orchestra. The accompaniment parts seem unmusically loud, creating for the modern ear, a strange, unmusical balance. And yet, Herva Nelli’s extraordinary voice and her endurance is absolutely stunning. Di Stefano, tenor, in the “Ingemisco” is sublime; Barbieri, mezzo-soprano, has an extraordinary voice and technique; and Cesare Siepi’s “Confutatis maledictus” is, certainly, one of the best of the bass performances in this reviewed collection. From this recording, with all of its defects, however, one can still hear the energy that Toscanini pulled from his players. And his energy is a vortex of immediacy.

Toscanini’s Dies Irae, the opening G Minor full tutti fff chords followed by the ‘frequency wrenching’ bass drum hammers, are quite spaced apart; that is, the power and sheer terror of “The Day of Judgement” is conveyed in the explicit ferocity that the maestro evokes from Chorus and orchestra, not in the speed with which he takes this section. Listen to Gergiev’s Dies Irae and you will hear a great opening but taken much faster. Toscanini clocks in at 70 bpm; Gergiev at 80 bpm. And yet, Gergiev’s overall Requiem performance time is 86 minutes; Toscanini’s 1951 recording, 77 minutes. This goes a long way to explain the tautness of the phrasing in Toscanini’s performance, the feel of a relentless push this creates in the listener and the sense of everything wound tight as possible. The immediacy and emergency felt in this performance does, however, betray a lack of sentiment, or shall I say, a lack of freer play permitted the soloists. One more example from Gergiev; tempi for both fugues, the double fugue in the Sanctus and the fugue in the Libera Me, are significantly faster than Toscanini’s, yet Gergiev’s overall performance time is 9 minutes longer. What’s the difference? Gergiev allows Renee Fleming in the recitative/chant section of the Libera me that leads to the great fugal section much greater freedom with this section. Toscanini treats the soprano recitative, in contrast to Gergiev, as a precise unyielding rhythm with text—no deviation. Toscanini does this with all the soloists.

Toscanini’s 1951 performance is still in my top 3 choices as a “must hear” recording of the Verdi Requiem. Who else can I place in this illustrious pantheon? What about Gergiev’s Requiem?

Gergiev’s 2003 recording of the Requiem is filled with magnificent orchestral moments, thanks to the Kirov orchestra; breathtaking speeds of dramatic sections, as already mentioned earlier; the choral strength of the Kirov Opera Chorus, particularly in relation to the speed of the double fugue in Verdi’s Sanctus, and 3 out of the 4 soloists show varying degrees of great musical strength. Renee Fleming does a superb job here as does Olga Borodina the mezzo-soprano. Ildebrando D’ Achangelo the bass soloist with a very pleasing voice, simply does not have, however, the gravitas to pull off some of the extraordinary moments that Verdi has given the bass soloist, the Confutatis maledictus, for example. The return of the “requiem aeterna” by the bass soloist in the Lux aeterna section is so profound a bit of writing that the voice must sound like the “supreme judge”, something like Eugeny Nesterenko, Rene Pape, Ferruccio Furlanetto or, of course, Cesare Siepi. But the unfortunate link in the quartet is Andreas Bocelli.

I will not stoop to some of the “ad hominem” attacks that have befallen Bocelli since this recording; suffice to say, as a so-called crossover artist from well-crafted popular tunes to Verdi: this is a bridge he ought not to have crossed. Bocelli has the range, accuracy of pitch and tuning under control, but, what he can’t control, nor change, is the very timbre of his voice. And here within the pantheon of pantheons—the tenor part for the Verdi Requiem—he should never have ventured. In the important a capella parts for the 4 part soloists, I’m thinking of the Hostias et preces and the ensuing a capella section for soloists, laudis offerimu, it is like listening to 3 operatic voices with the 4th part either missing or registering a timbre, completely contrary to the rest of the ensemble. No more to be said here. I still love Gergiev’s requiem; it is simply not in my top 3.

Gardiner’s Requiem with his Monteverdi Choir and L’Orchestre Revolutionnaire et Romantique present a different and refreshing sound of the Verdi. On balance, this is a very impressive performance where all of the top marks go to Gardiner’s use of the Monteverdi Choir. I don’t wish to short change the soloists or the competence of the orchestra, but it is the clarity of the choir that stands so tall in this recording. Let me give you but one example. In the great concluding Libera me, a movement most of which Verdi had written in 1868 on the death of the great Rossini—as his part of a group commemorative Requiem Mass that never saw the light of day—the choir, before the great fugue, intones a capella on an Eb major triad, then to a Db Major triad, the following text: Libera me, Domine, de morte aeterna, in die illa tremenda—moves to Db Major and continues: quando coeli movendi sunt et terra. Translation: Save me, O Lord, from death eternal on that awful day; when the heavens and earth shall be moved. Verdi marks this section with a double piano and with further direction, senza misura, without measure. Sounds straight forward, right? Well, this is why I am highlighting this moment in the Gardiner because what he does here was not thought of by Toscanini, nor Giulini, nor many others. Gardiner brings forth the consonants in the text like very few have done. Instead of smoothing the vowels and consonants into one mellifluous sound, Gardiner highlights even at a double piano, some of the more percussive vowel and consonant combinations. Truly, atmospheric. The only conductor I know who does this more impressively is Teodor Currentzis with his Musica Aeterna choir. This performance is only available presently through the Berliner Philharmoniker Digital Concert Hall; free, by the way until April 18th/2020.

Let’s come back to the Gardiner. Listen to his Sanctus and you will hear one of the best performances, in regards to clarity of text and balance between chorus and orchestra, on the market. No getting around it. Then listen to all of the Libera Me. Luba Orgonasova’s smaller soprano voice would not be my first pick for the soprano role, but as you listen to the complete performance her voice begins to fit this ensemble’s sound like a glove. The brutally high Bb sung at quadruple piano to a fermata just before the last recitative and the great Libera me fugue, she nails. The tenor Canonici is to my ear the weak link, but Von Otter and Miles are a musical plus. Once again the 4 part choral fugue which follows is stunningly clear with a robust speed that still reveals the text—utterly refreshing. These are memorable moments. For all of this, I put Gardiner’s Messa da Requiem in my top 3.

Pappano’s recording of the Messa da Requiem, released 2009, with the Chorus and Orchestra of the Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia requires our attention now.

The opening of Verdi’s Requiem of which I have not yet talked about requires a deftness and “the murmur of an invisible crowd” to set the mood of these extraordinary words: “Eternal rest give unto them, O Lord, and let perpetual light shine upon them.” The Santa Cecilia chorus’s dynamic range is in full display in this opening section; from the double piano and sotto voce opening to the testosterone-laden sound of the basses’ entry at “Te decet hymnus”—this is a remarkable chorus. The days of unsophisticated Italian opera choruses are over now. Just before the great tenor entry in A major with the “Kyrie eleison”, a contrast to the grave and somber a minor opening of the Requiem, there is a beautiful and dramatic choral crescendo that if done properly brings the tenor’s A major melody into stark and heartwarming relief. Pappano gets this right—completely. So many conductors allow the chorus a full blown forte for a full bar before the A major entry, not Pappano. He reserves this power and potential for beats 3 and 4 of the transition bar and then like a 747 flying overhead the contrast from the dominant of a minor to the A major is wondrous.

The Dies Irae is faster than Toscanini’s but balanced similarly—more inner voiced weight to the G minor chord, less pronounced piccolo part and very exciting. The stent. un poco a tempo is beautifully handled without grinding to a laughable slowness before the return of the “dies irae” motif. All done with consummate taste. Pappano’s handling of the 3 part trumpet solo section before the entrance of the chorus in the “Tuba mirum” is controlled and far less of a double forte than most other conductors; he reserves his hair raising wall of sound triple forte for the entry of the “Tuba mirum”. So well paced; so consummately dramatic.

Special praise has to be reserved for Rene Pape’s performance. His “Mors stupendit” is dramatically handled and is right up there in the ranks of Ferruccio Furlanetto, the bass soloist for Bychkov and Barenboim. One of the most sublime moments written for a bass soloist in the Requiem is the “Confutatis maledictus” and in the second repeat of the “oro supplex et acclinis” in C# minor, Pape sings with a breathtaking triple piano and a beautiful vibrato, certainly different from Furlanetto’s superb rendering of this text, but equally impressive.

Finally, we must point out the deft handling and clarity of the choral fugue sections of the Sanctus and Libera me. If Gardiner’s rendering of these passages creates a new standard for transparency, then Pappano, with his Roman chorus, is up to the challenge. The “Libera me” fugue section is as clear as one could ever hope for, with the statements and counterpoint beautifully balanced. Perhaps Pappano’s forces are helped by the acoustics of the new Parco della Musica where this recording took place; perhaps it is the musical vision of the conductor, perhaps both. The end result is a clear transparent sound that is difficult to beat. The great choral build up beginning with the bass motif “Dum veneris judicare…”, with the rest of the chorus answering back in the same text at pp, leading to the Tutta Forza in C minor technically fine. I’ve heard it with more punch, but Pappano takes the arrival at the Tutta Forza with the same beginning modestly slower then returning to the original tempo as does Muti and Gardiner. Very exciting and very dramatic. Pappano’s Requiem is the final recording to land in my top 3.

A final note; and thanks, dear reader, for staying with me so far. As true audiophiles and lovers of great music, we all know in our hearts there is no ONE perfect recording. All of the above listed recordings that I have selected for this review have extraordinary and deeply musical moments. Let me give you a few final examples.

The Barenboim recording has moments of special “magic” that no other conductor brings forth. Furlanetto is singing the “Confutatis” section; Verdi writes this section in c# minor, modulates to E major and at the end of the phrase “ gere curam mei finis” ends in E minor with a descending bass line and the same repeating eighth note pattern in the strings at double piano. A haunting oboe melody played by two oboes an octave part brings the Bass soloist back in. Absolute magic! Barenboim’s sense of awe here and intelligent balance of the forces brings out the greatness of Verdi’s writing.

Bychkov sculptures his quartets of soloists in the Offertario like no one I have heard. Too much of the large orchestral work is too controlled by Bychkov robbing the power of the music; but, the detail and the beautiful “chamber-like” sound he gets from his soloists in the a cappella parts is remarkable.

Does anyone have the same calibre of soloists as the classic and phenomenal recording of Giulini’s Requiem of 1963-64? In my opinion, no. Schwarzkopf, Ludwig, Ghiaurov and Gedda, an unrivalled team of legendary vocal power. Gedda showed that a superb tenor could be a great soloist and blend at the same time; that the tenor part of the Requiem wasn’t just an extension of Italian opera but was the Italian cantabile style in the service of the liturgy. Giulini’s recording should be in everyone’s CD collection.

History gets the last word. In response to Von Bulow’s acerbic and vicious comment, Brahms said that Von Bulow had finally undermined his own credibility and declared “Only a genius could have written such a work.” When Von Bulow finally heard the work 18 years later at a mediocre parish performance he was so moved he wrote to Verdi and apologized. Bernard Shaw, who had always admired Verdi’s music, suggested that none of Verdi’s operas would prove as enduring the Requiem.

No other Requiem in the history of Western music has manifested the deep contradiction of the Roman rite as magnificently as Verdi’s. This Italian voice has given us the light and the darkness of the Christian message and no matter our level of scepticism we revel in the theatre he has given us.